After All, Brevity Is the Very Soul of Wit*

“Be brief!” says Howard Rauch, author of Get Serious About Editorial Management.1 “Following this should be duck soup for most editors,” Rauch writes. “But that’s hardly the case.” What does Rauch mean by this? Should our sentences consist of only three words—noun, verb, direct object? Or should we seek for more, as the long form content movement progresses?

Primarily, Rauch references sentence structure and grade reading level. He writes of something called the Fog Index, a quantitative measuring resource I will have to check out. He brings up, what is for many of us, a fantastic point: how long are our sentences? What grade reading level are they written for? For whom are we writing?^

But how does this figure in to long form content?

Long Form Content

At first glance this long form business appears to be based around search engine marketing, but hark! What is the end goal of search engines? I find the answer to my question “What does a search engine do?” confusing:

Apparently, a search engine is a web index. That’s nice and all, but how does that help me? Web indexes in search engines provide us with results to our queries on the internet. So, let’s ask Google another question: What is the point of search engines?

The result can be found with an even better question: Why do people use search engines? Dummies.com suggests the top uses for a search engine are:

1. Research,

2. Shopping, and

3. Entertainment.

While my experience certainly does not support the ordering of that list, it definitely supports the content. (My experience rarely equates with the 99%, however, I can only guess that it does make up some part of that total percentage as someone, somewhere, does relate with my experience, probably that miniscule .00000001 percentage of people—I call them friends).

If those are truly the top uses of search engines, then it behooves the search engine to try and align the quality of their web indexing to match those user goals. If search engines are focused on users, then it follows that perhaps we should be too.

Why have I followed this train of thought so thoroughly? Because I focus quite a bit of energy on thinking about applying SEO guidelines to my work. And SEO best practices should be very aligned with content best practices. While search engine results can’t tell us why users are doing something, they can certainly tell us what they are doing.

And if what they are doing is spending a lot of time and energy on long-form pages, perhaps we should spend some time focusing on quality long-form pages.

There and Back Again**

Not too long ago, I recall breaking up long form pages of content. These pages were miles long—well the web equivalent of miles—with anchor links and “back to top” under every section. If long form is The Thing, why then did we change our pages a couple years ago, breaking up information into tabbed pages?

I tend to think we followed a design trend. Or perhaps it was the explosion of SEO-gaming tactics, writing multiple short articles about nothing—fluff punctuated by keywords leading to higher search results. There were also things like microblogging and tumblr.

Design-wise, in a desktop focused industry, it was a way of making vast amounts of information more visually palatable. The web however, as all other things do, evolves. What remains constant is the centrality of search engines in our lives.

With this brief reminiscence, we now ask: long form content, what are you now?

Long Form: 2,000+ Words

A return to Search Engine Journal indicates long form is primarily 2000+ words formatted in whitepapers, e-books, and how-to guides. Short form content, like blogs, social posts, and emails (although I’ve seen some reallllllly long emails…) are apparently also useful, often referencing this long form business.

The best length guidelines for content that I’ve found focus more simply around your audience. What are their needs? What research are they conducting? What do they need to know to make a purchase? What tasks will your content help them to?

Longer form content for webpages focus on these user tasks. What does our user need and how can we deliver that information?

In my work at University of Utah Health, we discovered in our content audits that pages packed with information approximately 1,600 words more or less in length performed very well, at least as far as number of visits and time on page. Whether these met marketing and conversion goals, however, is another story!

Duck Soup^^

Our mission then is clear: we must be brief—but not too brief—focusing on our users’ needs. We must write for our readers using well-constructed but not overly wordy sentences. Our brevity must be more than a haiku but less than a dissertation, and I like to think witty.

Shall we organize a duck soup tasting?

- 2017, Get Serious About Editorial Management, Howard S. Rauch, pg 120.

*A sentence that was for Shakespeare, indeed very brief.

^Note: I write this primarily for myself to study and consider the vocation of content. If you are reading it, then wow! Please continue!

**A reference to Bilbo Baggins’ recounting of his journey in The Hobbit. If you don’t know who hobbits are, you have missed out.

^^An idiom meaning something easy to do or accomplish, which became widely used after its use as a title for a Marx Brothers film in 1933

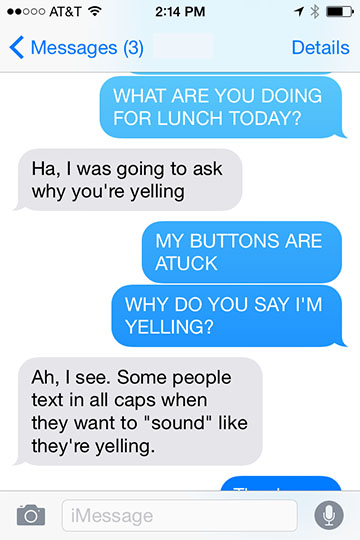

TEXT MESSAGING OR EMAILING IN ALL CAPS WITH YOUR CHILDREN/FRIENDS/CO-WORKERS, EVEN IF YOUR KEYS GET STUCK—THEY WILL THINK YOU ARE SHOUTING AT THEM.

TEXT MESSAGING OR EMAILING IN ALL CAPS WITH YOUR CHILDREN/FRIENDS/CO-WORKERS, EVEN IF YOUR KEYS GET STUCK—THEY WILL THINK YOU ARE SHOUTING AT THEM.