Outcome vs. Output, Quality vs. Quantity, Hybrid vs. Central

I was recently reading an article in Wired magazine that postulated time traveling (not surprising) and used it to put forth a commentary on our contemporary society (not surprising). They posit that a social scientist plucked from the eons of time is brought forward to 2019. Would said personage be “as astounded by our world as we like to think?”* The article author thinks not. And why not?

“Anyone familiar with the ancient Egyptian fixation on felines (cat statues, cat pictographs) and the mid-century American obsession with TV would at least have some pretext to accept that one of the largest conglomerates on the planet is the owner of a massive video site with millions of cat clips.”

— Zeynep Tufekci*

Now that was surprising! I could hardly contain myself!!! It’s totally true!! Our lives (or those of my friends and I) revolve around the feeding, cleaning-up-after, and placating of cats. That aside, humanity, if I can be so bold as to comment collectively, really hasn’t changed—despite the evolution of our tool set.

We remain as selfishly stupid and as supremely susceptible to the seven sins as at any time in history before. So where, I must ask, is the value proposition in that? And are ALL those cat clips really necessary?

Which leads me to the next rail car on my thought train: Outcome vs. output and how it contributes to value.

Outcome vs. Output

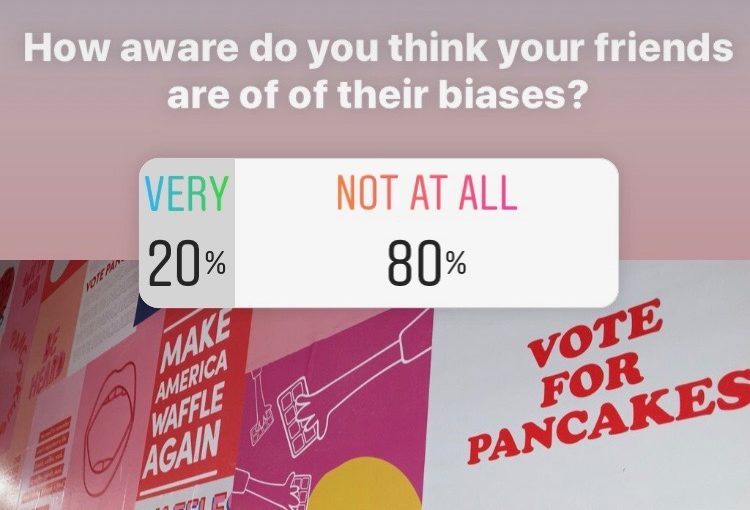

As has been documented many times over, we are a world obsessed with output. And our clients demand it. What they don’t tend to think about in marketing and content strategy is that to be truly successfully, content output must be matched up to a content strategy and an outcome. Otherwise, where is the value add?

To be truly successfully, content output must be matched up to a content strategy and an outcome. Otherwise, where is the value add?

Confession: A highpoint in my life is viewing a stymied subject matter expert, generally an MD in my industry, as I debate with them pros and cons of content output vs. content outcome. Does the content truly help us meet our goals? I’m sure my glee is palpable…

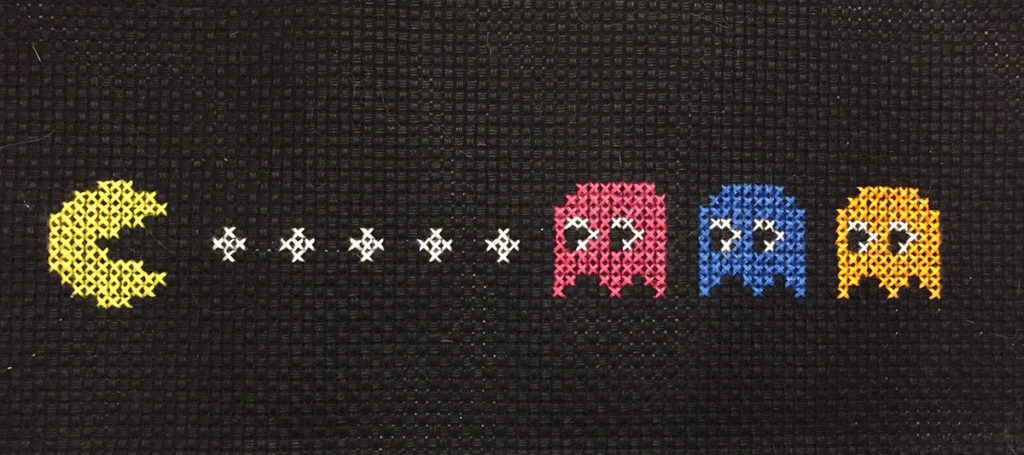

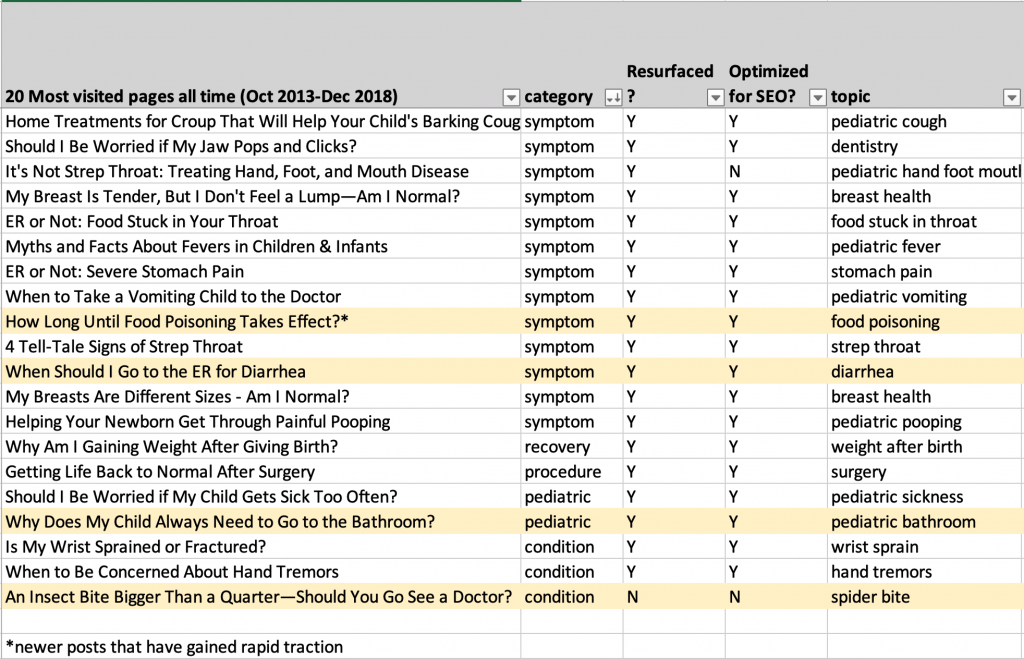

For example, here is some of our top performing content of all time: interviews with subject matter experts published with transcripts to our website.

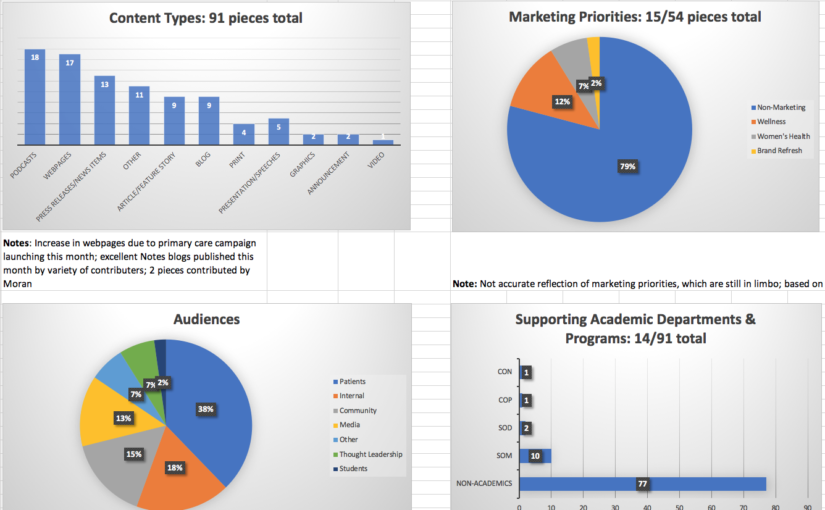

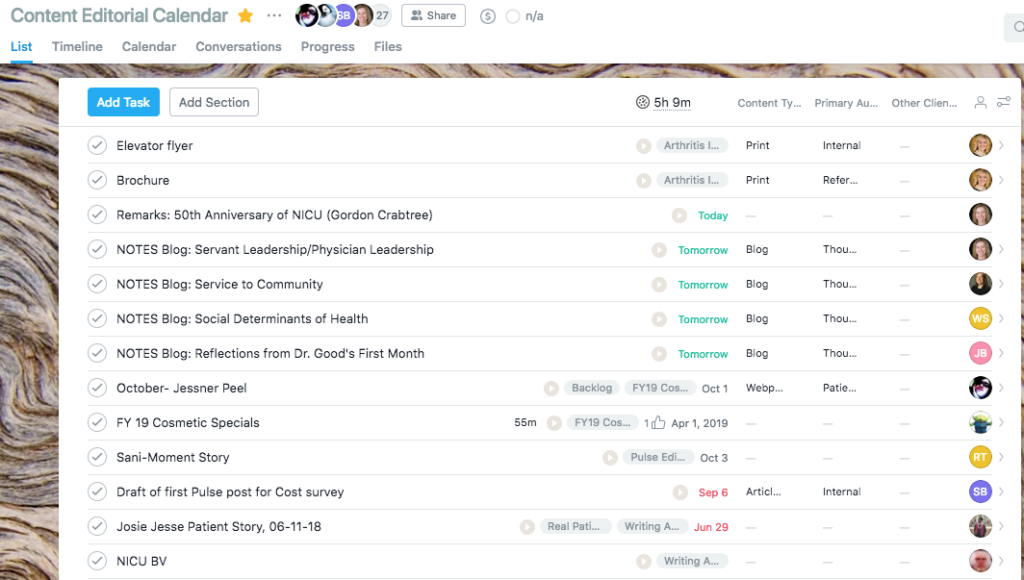

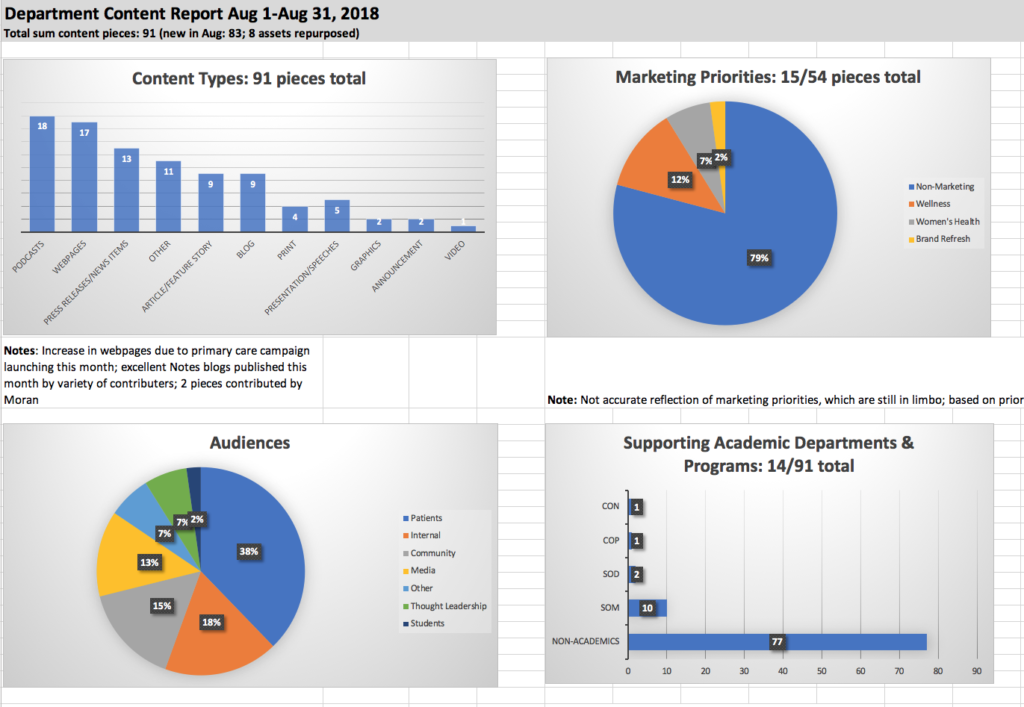

Out of all our content, approximately 30 assets (.002%) our of 15,000 drive almost a quarter of all our web traffic. (See Fig 1. Note that I added 10 of our top performing blogs to 20 of our interviews for the 30 assets, which I didn’t show in the figure—sneaky. Sorry about that. They do exist!!)

To me, this sparks multiple suppositions:

- We should be actively promoting that content as part of our ongoing strategy.

- This content clearly resonates with an audience and resonating with your audience is important.

- We need to create more MORE!

In slowing down to consider more fully however, are these really should-do’s or are they rather could-do’s? Where is this traffic going after it arrives? And what outcome are we looking for? The further research I conduct into this question, the more I question our content machine.

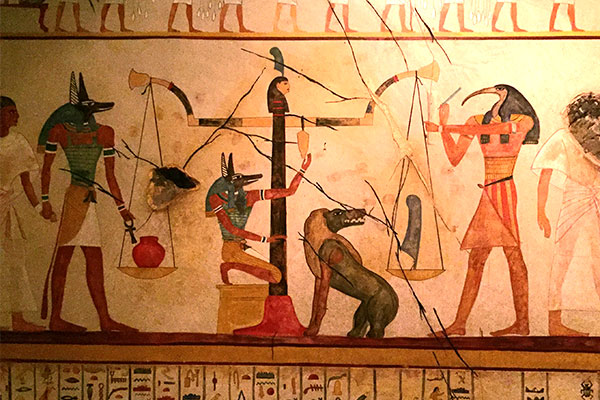

Egyptian balancing of the scales upon death: Anubis assisting the dead man vs. Horus, keeper of the underworld. Replica of a tomb in Beni Hassan at the Rosicrucian Museum in San Jose, CA, visited 2019.

Don’t get me wrong, I believe you must have that eternal balancing of the scales. A conglomeration of high performing cat clips was not established without much experimentation and mass quantities of cats. But I do believe we must create with an eye towards quality.

Don’t fret overly much about keeping the content scales balanced with both quantity and quality. A conglomeration of high performing cat clips was not established without much experimentation—and mass quantities of cats.

And I’m grateful to note that in my organization we are also becoming obsessed with outcome and quality of outcome.

Quality vs. Quantity

I find that sometimes our higher quality content is not necessarily our highest performing nor are we producing it in high quantities. Here I must pause and identify a value add for our organization.

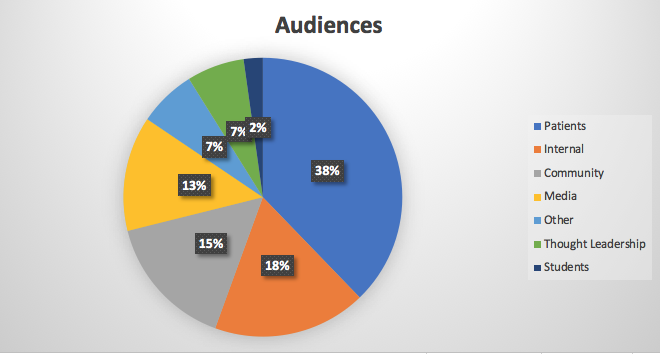

For my team, we have determined that measurable outcomes consist of, essentially, lead generation. How many clicks on the “Schedule an appointment” button can we track? How many taps on the scheduling phone number? Can we get all this data lumped together onto a dashboard that reflects in a quantifiable number the difference our team is making?**

Alas, there are major gaps in our data collection. We cannot track if an appointment was actually requested once a lead has called the phone number. Nor can we track if a request form submission has led to an appointment scheduled. We also cannot connect whether a particular lead driven by video or written content has resulted in a higher value patient for the organization (namely resulting in a surgery—something our specialists find extreme value in—and not only for the revenue).

And for other teams creating content in our organization, quantification and value remains somewhat mystical. What is the value of that high performing content that drives so many site visits? Since it was technically created in the name of brand recognition, how can it hurt us to have such massively successful content?^

One also can’t negate the benefit of this content for our internal stakeholders. Is some volume necessary to keep the peace even if the long-term value is negligible? (Btws, I’d say yes. If you have to create something for a stakeholder to give them a twinge of joy or that, hopefully, leads to data collection on why it’s not a value add—BY ALL MEANS VINDICATE YOURSELF. And if you fail, it was in the spirit of experimentation. We must keep our sense of humor about us.)

But still I do pause to wonder, could quantity hurt us? When does quantity negate a value add? (More on that in an upcoming post as I have been watching some experimentation in our content ecosystem.)

When does quantity negate quality and therefore its value proposition?

Sidenote in the name of quantity: #DYK that the monuments of ancient Egyptian culture morphed from pyramids of massive size to smaller hidden tombs to temples that remain UNESCO heritage sites to this day? We all have heard of the Egyptian obsession with a life after death, but did you also know that they massively stockpiled provisions and small representations of servants (ushabtis) and the like to aid them in their next-life journeys?

Sometimes I can’t help but think that the ushabtis and cats mummified for this cause, while probably high in quantity and supportive of Egypt’s economy, probably did not return the value expected by their purchasers…

Enough already now though of the musings and questions and assumptions. Let them have solutions! Let us unsheathe the teeth and claws. Which of these propositions leads in a bid for value?

Hybrid vs. Centralized

I dare you to identify frameworks in your life that are hybrid partners vs. centralized in nature. A few come quickly to mind:

- Pointillism: The foray of Georges Seraut into complete paintings made of dots that unify to create figures and forms (the forerunners of pixels).

- The EU: A union of countries vs. Great Britain standing independent. #Brexit

- Fashion: Mixed prints over matchy-matchy, both of which schools of thought vie for dominance.

- The US of A: An experiment in democracy that resulted in independent states in tenuous balance with a unified (supposedly) federal government.

- Google: Which business model focuses on global dominance but also opens numerous projects and businesses in the name of innovation and experimentation.

- Alpha cat (me) vs. baby cats in my household.

Notice that in all of these situations, there are a variety of models, from rebel (Seraut’s points) to central (Google) to hybrid (the US of A). There is no clearly dominating model that seems to work better than any other.***

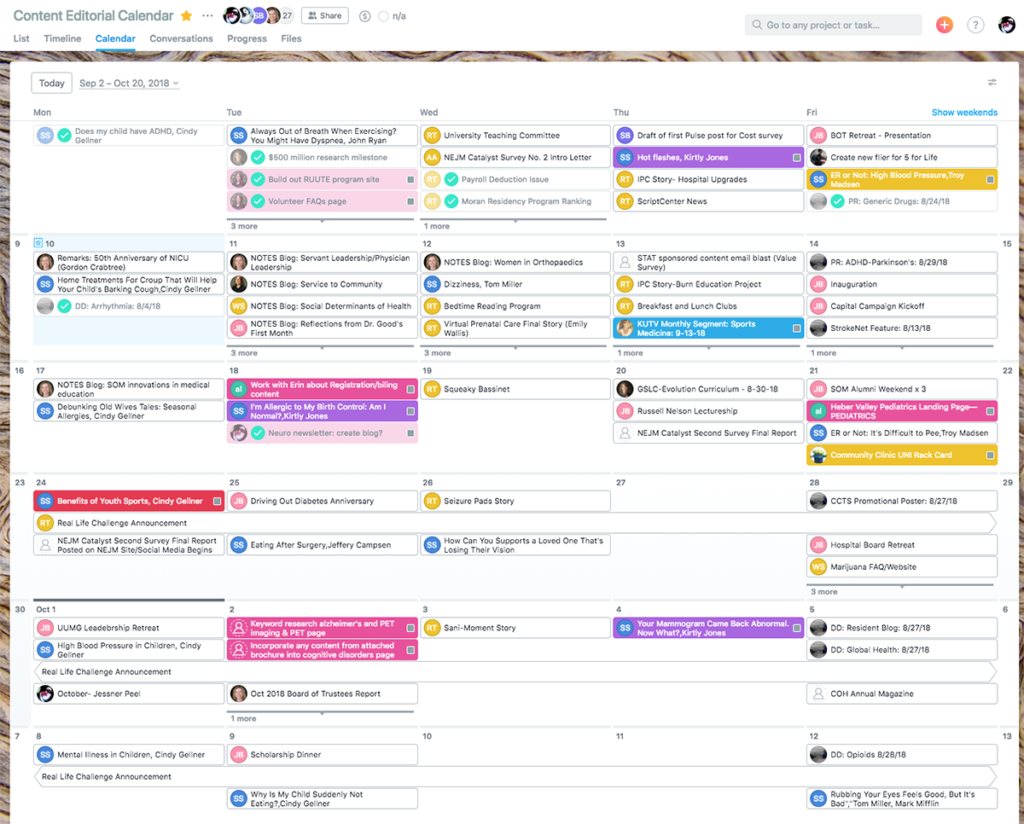

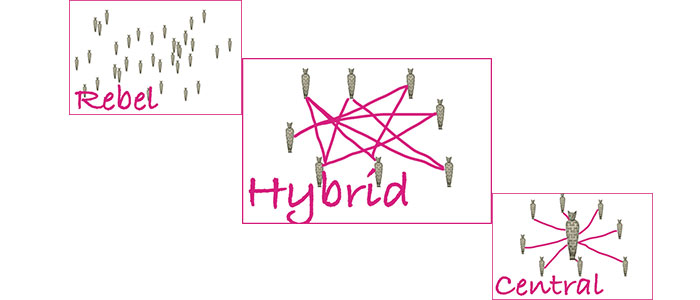

Dennis Shiao, for Content Marketing Institute writes that companies, much like those parallel examples above, organize around content in three different models (as illustrated in Fig 2):

- Rebel

- Hybrid

- Central

And here I make my stand and offer my solution for the pursuit of value: With the caveat of leadership influence, I make a bid for the hybrid model.

I proffer the proposition that true value lies in a balance between the content created by rebels and the overlord conjointly, for these reasons:

- Agents of chaos can sometimes make amazing content.

- Without centralized and singular guidance, mavericks can lack backing to move a project forward and harness the quality of their content for the most value.

- Too strongly centralized methodology can establish a series of hoops so discouraging that it precludes any creativity or timeliness.

- Conflict between methodologies can lead to sparks of genius that would otherwise never achieve combustion.

And therefore, my value proposition: Don’t dismay if you have content creators who aren’t following all the best practices or centralized standards. Some of the stuff they create is amazing and resonates with an audience.

Do strive to represent a unified brand and style guide to represent consistency and quality in your work. Do work towards data collection and quantification of output in the hopes of demonstrating good practices.

Hybridize and experiment.

My value proposition: Work towards a hybrid content model where you empower individuals but maintain a strong centralized brand and structure around desired content outcomes.

While I like to think that I am the alpha (and can site evidence towards this theory), I must acknowledge that I often bow to the vagaries of my felines. Without their hidden depths and uncanny ability to surprise me, however, I would not be such a delightfully centered eccentric.

We are, of course, each a singular sensation.

*”Free Riders” by Zeynep Tufekci. Wired Magazine Sep 2019

**Let me refer you here to an amazing podcast from Brain Traffic with Kristina Halverson and some content data analysts at Harvard who have been able to create such a magnificent dashboard. I am simultaneously immensely envious that they have an actual data scientist and extremely chuffed that my department is also dabbling in this. Democratizing Data at Harvard

^I want to assure you that I have plans around establishing and assigning a measurable value to this. If only I could find the time for the analysis!!

***I’m ignoring the fact here that Google basically owns all of us.